A Stillborn Deliverace

“But the gift of freedom does not operate according to circulatory or cyclic models of exchange; there is no ebb and flow, and the slave has no say in the structuring of the exchange relationship. Consequentially, the gift of freedom is end stopped, it isa one-way traffic, it is all give and no take, it is a stillborn deliverance, and . . . it is above all a statement of power.”

-Marcus Wood, The Horrible Gift of Freedom

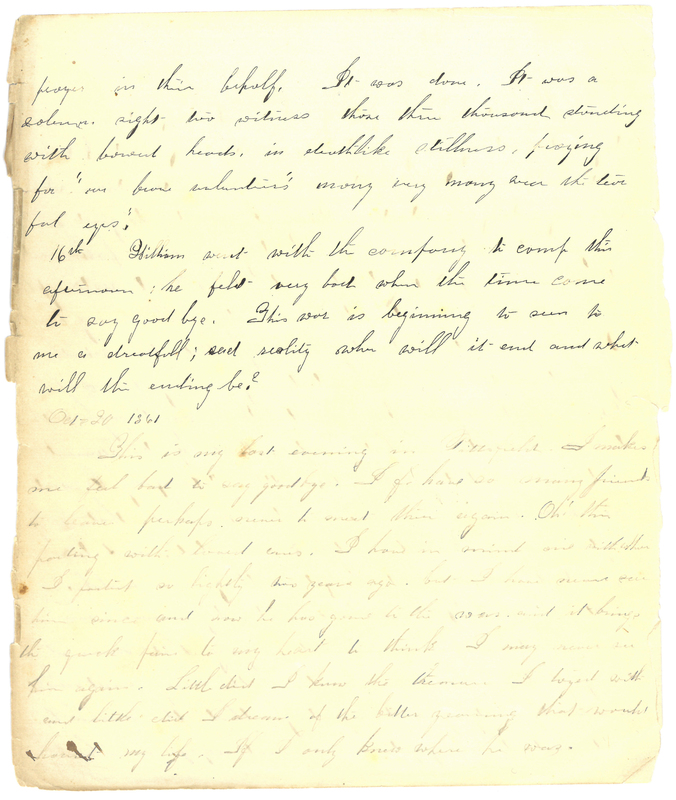

A student at Oberlin College from 1859 to 1861, Emilie Palmer’s education aligned almost directly with the beginning of the Civil War, thus implicating her both personally and politically in the local efforts, debates, and activisms of the day. Her diary, which was donated to the Oberlin College Archives by her granddaughter following her death, offers unique insight into the effects of the Civil War—and by extent, the abolitionist movement—on small town life. Writing from a position of relative detachment—women, after all, were required to stay at home while their husbands, fathers, and male peers went off to fight—Palmer nonetheless managed to capture the anxieties, dialogues, debates, and expressions of comradery that underpinned Oberlin’s quest for civil justice, and the shifting role of female citizens that followed.

Though she never explicitly identifies herself as an abolitionist in her entries, it is evident that Palmer was exposed to and influenced by Oberlin’s abolitionist movement. Her first entry from the diary, dated July 8th, 1859, details the celebration that followed the pardoning of the local men that had participated in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue. A now revered moment in Oberlin history, the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue marked a turning point in Oberlin’s public commitment to social justice, making clear and reputable the town’s collaborative effort to resist, protest, and concertedly act against the institution of slavery. When slave-catchers in neighboring Wellington abducted John Price, a fugitive from slavery, a mob of male Oberlin residents decided to storm the premises, an act which enabled Price to escape recapture. Subsequently jailed for their efforts, the thirty-seven Oberlin men were lauded by their hometown as heroes, and have since (collectively) become the face of Oberlin’s abolitionist movement.

Though undoubtedly a significant event with lasting consequences for both the white and Black communities of northeast Ohio, the (Oberlin) archive’s recollection of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue is adversely confined. Most of the photographs, documents, and artifactual evidence from the event feature white men as the central subjects; people of color (who were indeed both participants and supporters of the Rescue) and women are almost entirely excluded from the narrative. Emilie Palmer’s diary, then, is a critical piece of history, as it speaks to the role of women (and lack thereof) in the abolitionist movement, as well as to the day-to-day acts of civil protest and remembrance that have otherwise gone unrecorded. Palmer’s entry recounting the celebration of the rescuers begins:

The rescuers[”] were pardoned, and were coming home on the evening train. There was joy in Oberlin such as is not witnessed every day. At prayers notice was given of the meeting in the evening and one of the Professors said that Mrs. Dascomb gave the ladies permission to attend, and also if any of them felt strongly moved they might go with the procession to the depot. I think some of them must have been moved for nearly all the students were with the three thousand who assembled to welcome the heroes home; when they alighted from the cars a shout arose that made Oberlin sing, Prof Monroe was called out and from the platform pronounced an eloquent and thrilling speech in welcome of the prisoners. The procession then formed, with Father Keep + Father Gillett in advance, and the vast throng with banners flying moved to the stirring music of the Oberlin band towards the church.

In this single opening paragraph, Palmer depicts Oberlin as a place united in its progressivism. She describes the spectacle of the celebration: the preparatory prayers, the speeches, the elaborate procession, and—perhaps most interestingly—the demographics of the celebration’s attendees. Despite first having to secure “permission” in order to attend the procession, the “ladies” of Oberlin showed up in large numbers. As Palmer frames it, their presence and support was imperative to the magnitude of the event. A testament to both the spiritedness of Oberlin’s abolitionist movement and the strength of women as independent actors amidst a party of men, Palmer’s entry from this day is a crucial resource in the ongoing historicization of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue, on both an institutional and individual scale.

In her entry from September 16th, 1861, Palmer’s words are much more somber. The entry reads:

William went with the company to camp this afternoon; he felt very bad when the time came to say goodbye. This war is beginning to seem to me a dreadful, sad reality, when will it end and what will the ending be?

Written a few months into the Civil War, it is apparent that the spiritedness which had been so prevalent in Palmer’s description of the Oberlin abolitionist movement just a few years prior had, by 1861, been reduced to a disheartened pessimism. In the entry preceding this one, Palmer describes her graduation from Oberlin, an occasion which was apparently dominated by the news that many Oberlin soldiers had died in battle. She writes, in obvious despair:

At the close of the exercises Wednesday forenoon someone handed Prof. Morgan a note; saying that nine of the graduating class were absent in the army, and might be even then dying; and requesting that the names be read and the congregation rise and engage in silent prayer in their behalf. It was done. It was a solemn sight to witness those three thousand standing with bowed heads, in deathlike stillness, praying for “our brave volunteers”, many very many were the tearful eyes.

Upon graduating from Oberlin, Emilie Palmer became a teacher, a profession which she stayed dedicated to throughout and after the end of the Civil War. Despite the insular, hometown focus of her diary, Palmer’s story is nonetheless a remarkable one. Her writings serve as an entry point into the psyches of the (Oberlin) women who were implicated in but often looked over as being part of the abolitionist movement leading up to and into the Civil War period.

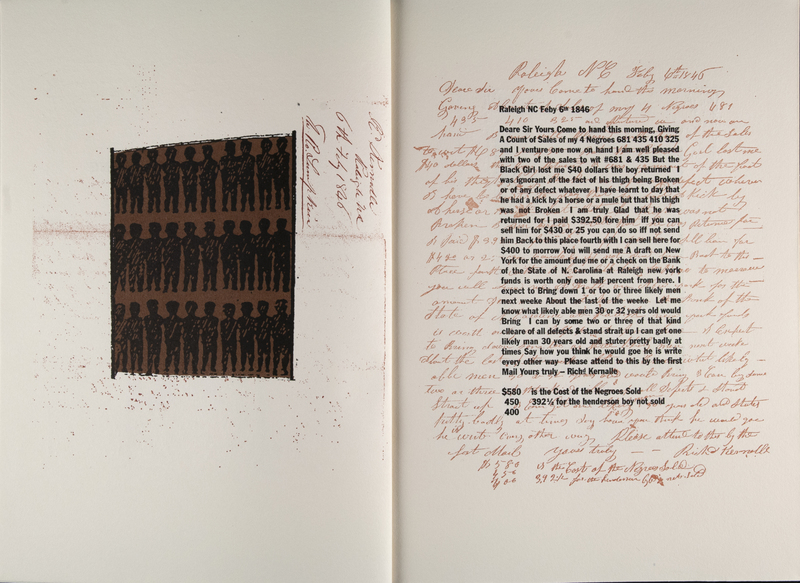

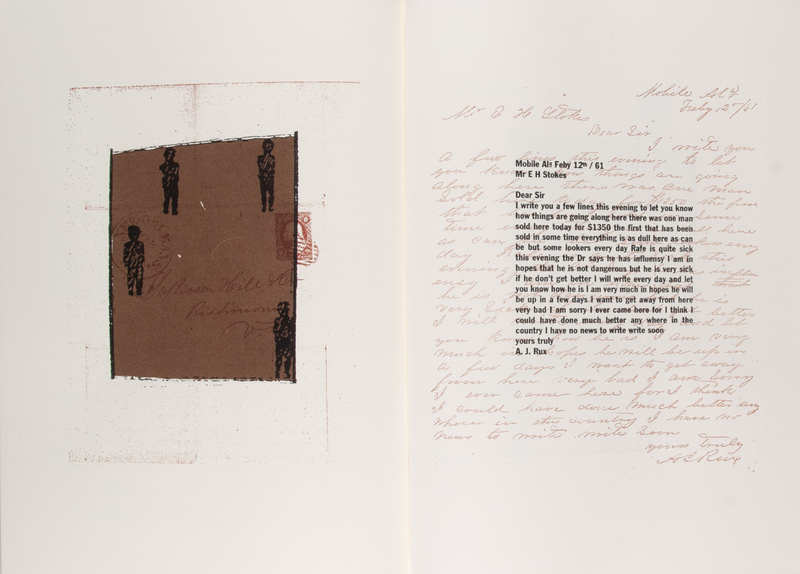

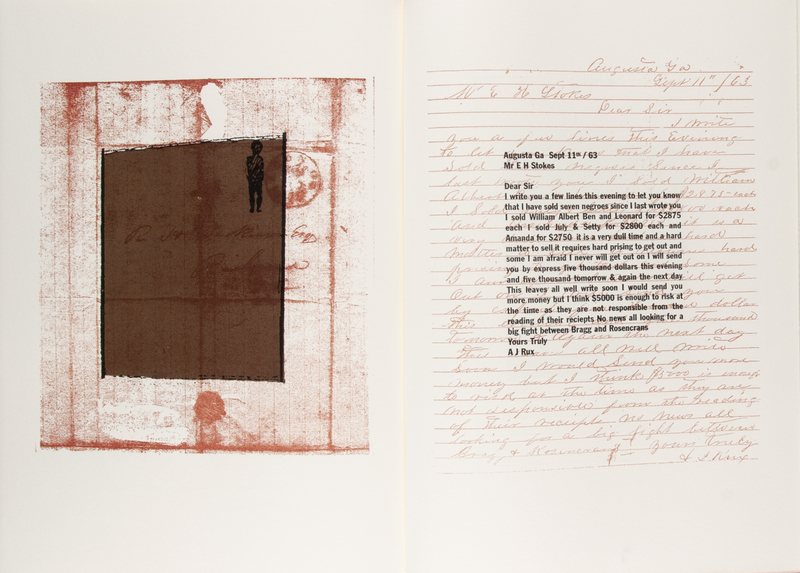

The Business Is Suffering utilizes the form of an artist book to compile, contextualize, and create visual irony vis-à-vis archival remnants of the slave trade. Maureen Cummins found the inspiration for the book after stumbling upon a series of letter correspondences in the American Antiquarian Society, the contents of which detailed the buying and selling process among slave traders between the years 1846 and 1863. The letters, which are arranged chronologically in the book, begin in a casual, matter-of-fact tone; Rich Kernalle, in 1846, writes about how he is “well pleased” with two of his “sales,” by which he means two slaves, whom he identifies by number: “#681 & 435.” This blunt, careless language of commodification is used throughout the letters; one begins to understand that this dehumanizing rhetoric is a device used by the sellers to distance themselves from the acts of violence which they are (indirectly, but no less consequently) committing with every sale.

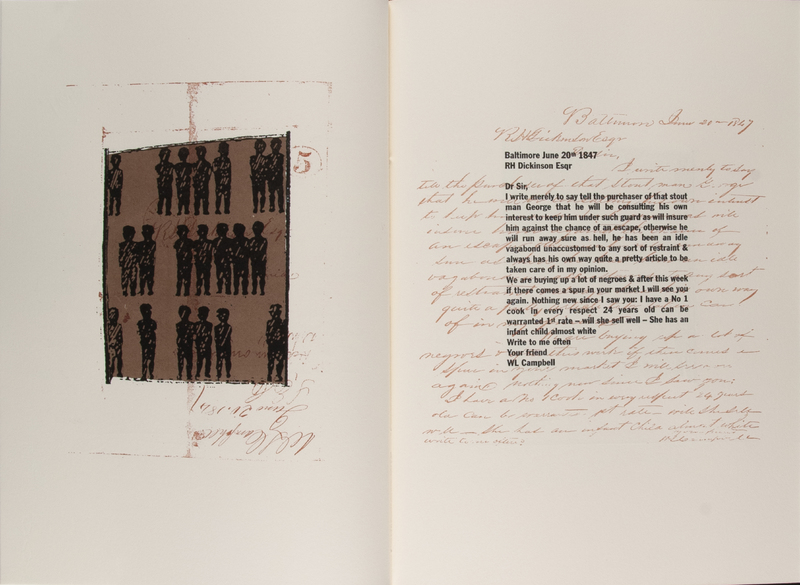

Read in order, the letters tell the story of the decline of the slave trade leading up to the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. By 1861, the letters are desperate and forlorn:

There was one man sold here today for $1350 the first that has been sold in some time everything is as dull here as can be...I am sorry I ever came back here for I think I could have done much better any where in the country…

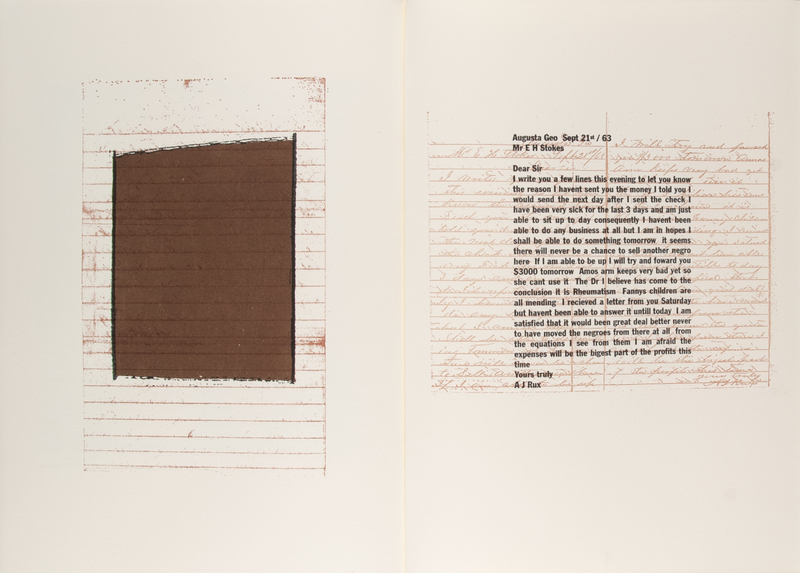

The last letter is dated September 21st, 1863. It begins:

I write you a few lines this evening to let you know the reason I haven’t sent you the money I told you I would...I haven’t been able to do any business at all...it seems there will never be a chance to sell another negro here…

On the pages opposite the reproduced letters are screen printed graphics created by the artist: silhouettes of bodies packed closely together, drawn in a sketchy style so as to obscure any defining, expressive features. Reminiscent of the infamous, widely reproduced Brookes slave ship diagram, the graphics can be read as a kind of abolitionist propaganda, a visual representation of the spiritual and corporeal that the corresponding letters have chosen to replace with numbers. As the letters move through time, the bodies begin to disappear from the page. By the end of the book, opposite the letter quoted above, the bodies have entirely disappeared; only a blank square of brown remains.

Cummins’ The Business Is Suffering layers historical documentation atop abolitionist imagery, culminating in an artistic depiction of the decline of the slave trade, and the emergence of freedom that arose, quietly but simultaneously, because of it.