Imagine a Free State

“As I understand it, a history of the present strives to illuminate the intimacy of our experience with the lives of the dead, to write our now as it is interrupted by the past, and to imagine a free state, not as the time before captivity or slavery, but rather as the anticipated future of this writing.”

-Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts”

These works reflect on Oberlin’s lengthy history of anti-slavery advocacy. As a town and institution, Oberlin has been celebrated as a center promoting abolitionism and activism. The following archives display instances of both activism and commemoration of anti-slavery efforts, from the 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue to the 1980 Oberlin Winter Term project that retraced an Underground Railroad route. The certain dates and specific media of these materials reflect actions to review complicative notions of the archive.

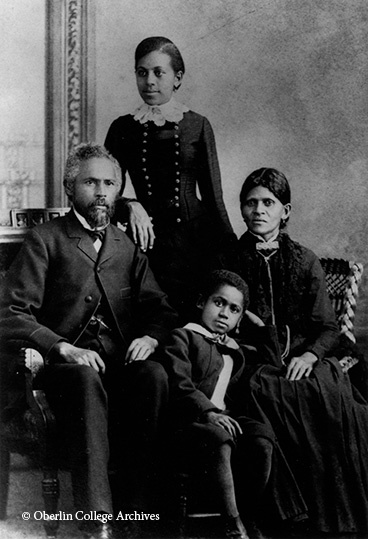

The photograph at left depicts John Scott, an emancipated man from North Carolina. Scott came to Oberlin in 1856 after his emancipation (the details of when and how are not documented). While in Oberlin, Scott worked as a harness and trunk maker, eventually owning a store in town. His participation in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue is also noted in the Oberlin Archives. Scott’s employee, Lewis Sheridan Leary, informed him about the capture of the fugitive slave, John Price on September 13, 1858. Alongside Richard Winsor, an Oberlin student, Scott traveled by horse and buggy to Wellington in order to help rescue John Price. Scott was ultimately imprisoned with the other Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers at the Cuyahoga County Jail. The history of John Scott is compelling, not only as a participant in the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue but also as a black business owner in Oberlin. There is not much additional contextual information regarding John Scott’s personal history, besides the documented information on his occupation in Oberlin. The photograph simply presents a portrait of Scott, his wife, and two children. After Scott’s death, he was buried in Oberlin’s Westwood Cemetery. This photograph holds visual documentation of Scott, as well as emphasizes the various roles that black residents held in Oberlin during the pre-Civil War period. A radical image of blackness, the photograph additionally brings to light Scotts' personal valor, as photographs were expensive to produce in the 1850s. Scott is a man with means and is proud to be commemorated through this form of historical documentation. It is essential to recognize the involvement of Black people in the Oberlin community during this time, especially those who were emancipated or fugitive slaves.

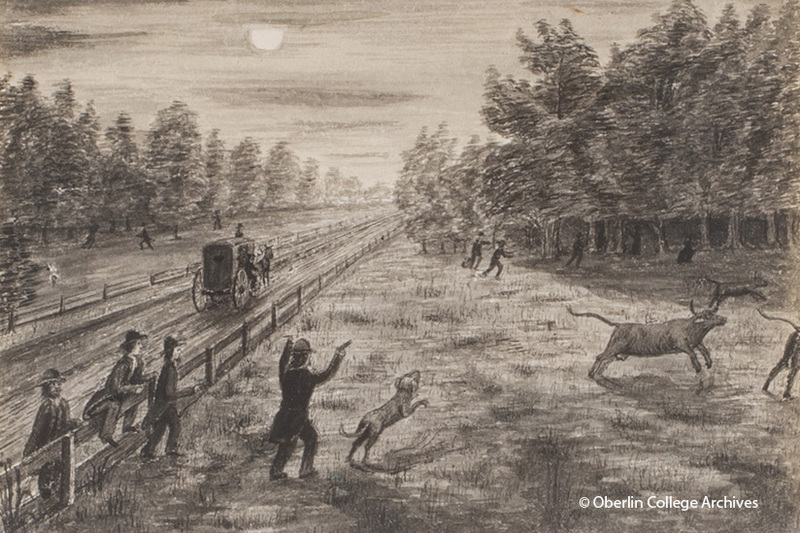

The Confidence Game: The Underground Railroad Near Oberlin, exhibits a scene of Oberlin abolitionists dissuading slave-catchers from capturing runaway slaves. This drawing was produced by Charles H. Churchill, who was a professor of Mathematics and Philosophy at Oberlin College from 1856 to 1897. It is also known that Churchill was the architect of “The Soldiers Monument,” which was built on Oberlin College’s campus in 1870 (torn down in 1935) and served to memorialize the ninety-six Oberlin men (fifty-five of whom were Oberlin College students) who were killed in the Civil War. Though little is known about Churchill, The Confidence Game perhaps can be interpreted as his clear support of abolition. The drawing positions an abolitionist in the center of the scene leading three slave-catchers over a fence and directing them towards two “made-up” runaways, instead of towards the real fugitive slaves who are racing away in the background. A carriage marked “Wellington” is depicted as well; this carriage can be assumed to be used by the slave-catchers, who would have used it to haul the captured slaves to Wellington, Ohio, where there was a train that would have brought them back to the south. This tactic used by Oberlin abolitionists can be interpreted through the drawing’s title as a sort of “confidence game.” It is unknown whether this phrase was used by abolitionists in Oberlin to describe their protection of runaway slaves, but Churchill’s drawing in whole helps visualize the significant anti-slavery strategies used in the town. The drawing’s 1876 date historically contextualizes it as a celebration of Oberlin’s abolitionist history, rather than a contemporary scene.

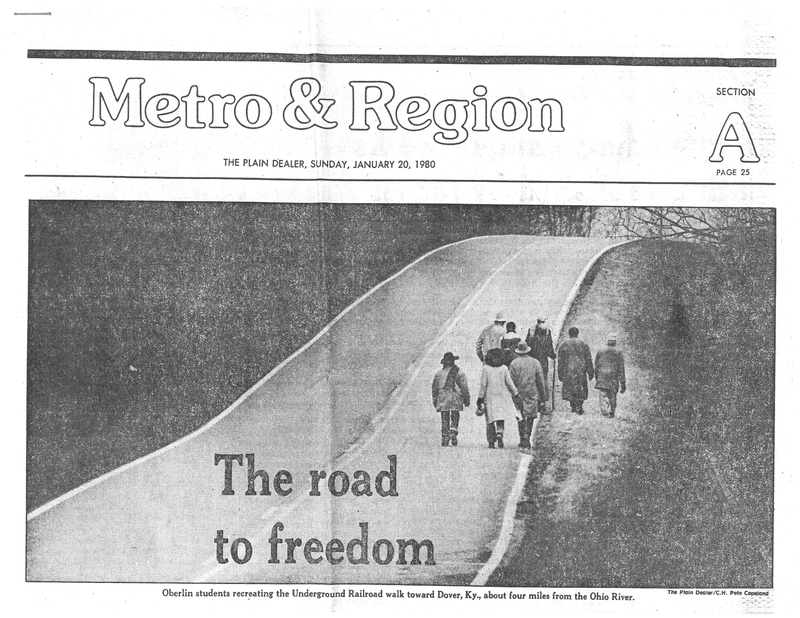

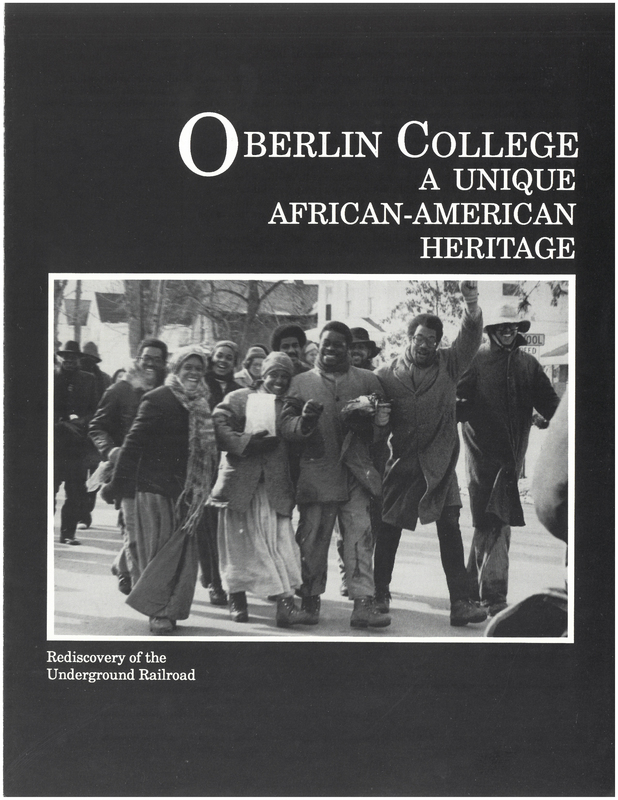

The two documents regarding the Winter Term project that nine Black Oberlin students participated in during January of 1980 exhibit a more current act of remembrance. This project involved the recreation of an Underground Railroad route beginning in Greensboro, Kentucky, and ending back up in Oberlin. The route was taken on foot and was 420 miles long; the trek took 33 days for the students to complete. The nine students involved in the project were David Hoard, Lester Barclay, George Barnwell, Gale Ellison, Herman Beavers, Marzella Player, Larry Spinks, Richard Littlejohn, and Adrian Banks. This project does not speak for the enslaved people who gained their freedom by trekking Underground Railroad routes, but deems the historical memory of slavery in the United States and Oberlin’s role in the Underground Railroad crucial to the project’s message of ancestral and institutional honor. The photograph on The Plain Dealer cover displays the students beginning their trip retracing the Underground Railroad route. The inclusion of this document highlights the amount of national press coverage the Winter Term project received. The cover page brochure entitled “Oberlin College: A Unique African-American Heritage” is also shown; this brochure was given out during a day of celebration held after the nine students’ return to Oberlin. The celebration incorporated presentations, poetry readings, and songs to commemorate the completion of the students’ project in addition to reflecting on slavery’s past and continuing legacy. By examining the visual resonance between The Plain Dealer’s cover image of the Oberlin students and Churchill’s drawing, The Confidence Game, a hopeful expectancy is held for reevaluating archival material.