The Kneeling Slave

“Hence, the sympathetic exchange that the kneeling slave invites not only humanizes the slave but also bestows power and privilege on his benevolent interlocutor."

-Teresa A. Goddu, "U.S. Antislavery Tracts and the Literary Imagination"

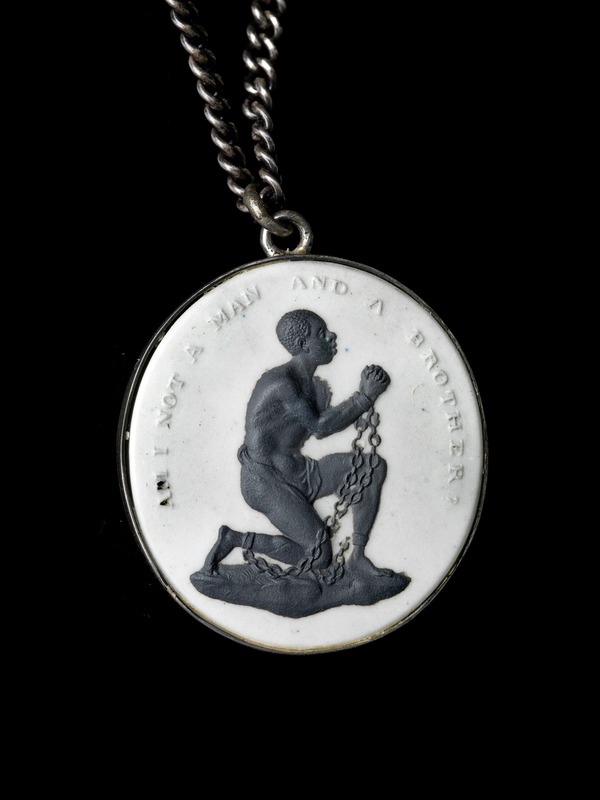

“Am I Not A Woman And A Sister” reads over a kneeling enslaved Black woman who holds her chained hands up in supplication, altogether engraved upon the class seal. The figure consciously echoed the design of a kneeling male slave, adopted in 1787 as the official seal for the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in England. Josiah Wedgwood, an influential member of the London Committee, and William Hackwood, the chief modeler at Josiah Wedgwood's pottery factory and the designer of the seal, later adapted the design on neoclassical-style medallions which presented a black cameo figure on white jasperware. As Robin Reilly explains, jasperware, as a white stoneware intended to resemble porcelain, was “especially suited to neoclassical ornament and appealed to cultivated taste in the eighteenth century.” The medallion soon became popular and fashionable among the middle and upper classes in England. The production of an array of settings and colors for the kneeling slave cameo suggested an extensive market need, and according to Michael Craton, more than 200,000 kneeling slave medallions were sold between 1791 and 1792. Working like political campaign buttons, the medallions gained popularity with the efforts of early abolitionists to attract public interest in their movement. As J.R. Oldfield points out, “this simple device became a form of abolitionist shorthand, a visual cue that made explicit the relationship between abolition, consumption and popular politics.”

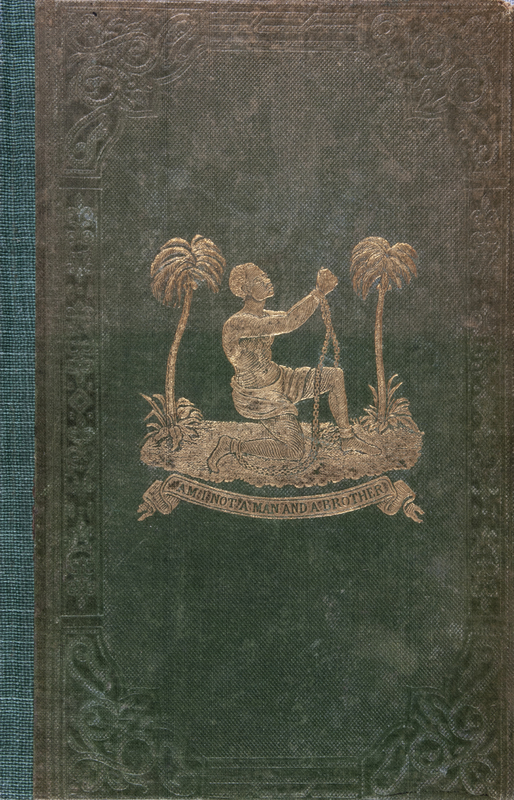

The image later crossed the ocean to be propagated in the U.S. In 1788, a consignment of the cameos was shipped to Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia. It has since become one of the first, and most iconic, anti-slavery iconographies in the eighteenth century and endured for much of the nineteenth century, attaching itself closely to the American abolitionist debate and movement and affecting how Black people were perceived on both sides of the Atlantic. It was replicated in prints, pendants, commemorative coins, oil paintings, newspaper headings, domestic material objects, as well as the cover of British abolitionist author Wilson Armistead's book A Tribute for the Negro, published in the United States in 1848. Compared to the original iconography, two palm trees were added to the image on the book cover, which reinforces a landscape of the slave trade. In this book, Armistead explains the “sin of slavery” and rejects notions of the correlation of intellectual ability to skin color.

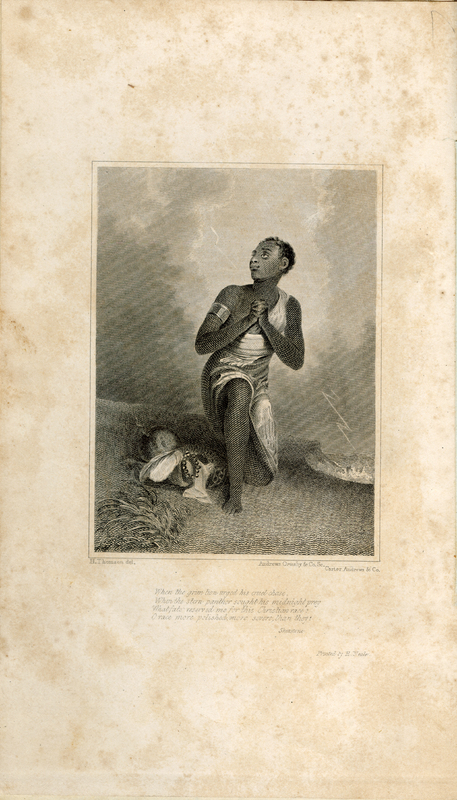

Adopting a similar posture as shown in the enslaved Black woman on the glass seal, the print on the left hand side in the case depicts Inna, a young, Black woman kneeling and praying amid a storm. The print was first published to accompany the short story "The Booroom Slave," written by Sarah Bowdichin 1828. In the story, Inna, the daughter of a chief from Booroom (a region of north-west Ghana), is abducted by slave traders. She escapes from the enslavement and begs not to be captured again along the shore. An Englishwoman rescues Inna, and the story ends by Inna converting to Christianity and returning to Booroom. The image of Inna mirrors the image of “Am I Not A Woman And A Sister” in that it was originally created for, and primarily consumed by, a middle and upper-class white audience. Indeed, the story and the print was first published in the gift book Forget Me Not. Gift books are lavishly decorated books gathering essays, fiction, poetry, and of course illustrations; they were a display of cultural capital and were especially popular among the elite British women as gifts in the nineteenth century. Lydia Maria Child, the American abolitionist, later propagated this image by using it as the frontispiece of her book An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans in the 1830s. Shenstone's poem, discountenancing the slave-trade, is quoted beneath the image: "When the grim lion urged his cruel chase,/ When the stern panther sought his midnight prey/ What fate reserved for this Christian race?/ O race more polished, more severe than they!” However, this book, as one of the first significant abolitionist texts written by women, was controversial when it first came out. The book angered Child’s readers who rejected abolitionism and undermined her successful career in children's literature.

The iconography of a kneeling Black figure is complex not only because of its transatlantic journey from Britain to America and its history of politicization and commodification, but also because it generates a visual contradiction of how to present Black bodies in antislavery dialogues. On the one hand, as Ezra Tawil notes, to depict the Black body in a kneeling, docile state "deployed the sentimental mode to humanize the slave to picture antislavery as a moral force.” It successfully acted as a visual strategy to promote antislavery ideology and political movement. On the other hand, the pitiable gesture given to a Black body by a white abolitionist deprived enslaved people of their autonomy and subjectivity, and underscored the perception of Black inferiority. As the question “Am I Not A Man And A Brother” or “Am I Not A Woman And A Sister”posed, the kneeling slave is begging the interlocutor's sympathy and the “gift”of freedom. As Teresa A. Goddu affirms, “the sympathetic exchange that the kneeling slave invites not only humanizes the slave but also bestows power and privilege on his benevolent interlocutor.”

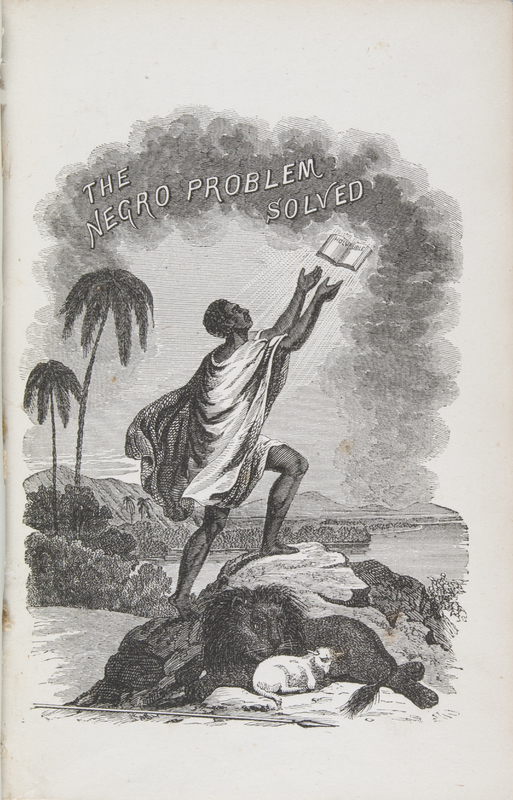

Moreover, the enslaved man's posture with one knee on the floor and two hands praying towards heaven combined the idea of gratitude and the Christian theme of conversion. Recalling that Sarah Bowdich promised Inna a happy future by letting the young Black woman in her story converting to Christianity at the end, a similar price of freedom is asked by the American writer, Hollis Read in his book The Negro Problem Solved. Published in 1864, one year after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, the author posed the question in the book's preface, “What shall be done with four millions of ex-slaves?” Then he answered the question by arguing that the future and hope of Africa lies in the “prospect of a Christian negro nationality.” The print on the frontispiece of the book further illustrates the author's argument. It presents a Black figure, with both arms outstretched, striding toward a rock. A book with an inscription hovers above his hands. The Black figure is devoted to honoring the text in the air, like how Christians are conventionally depicted to honor the Bible. The inscription “The Negro Problem Solved,” recalling the book title, appears above in the clouds and among the beautiful landscape with seashores and palm trees in the background, indicating a bright future of Black people under religious conversion. The Black figure wears a white Christian robe, and he has discarded his weapon in the foreground. The lamb and the lion lie down in the frontal scene generates an active Christian symbolic device related to peace. As David Bindman affirms, “Like the deserving poor, or unfortunate prisoners, it was intended that they [slaves] would repay the act of magnanimity by eternal devotion to their civilized masters or mistresses, and would, of course, adopt their masters’ religion.”

Unlike the slave ship, another iconic abolitionist image in the eighteenth century and after, being reused and reprocessed by so many modern and contemporary artists, we see very few examples of the reinterpretations of the kneeling slave. To some extent, we can argue that the passivity conveyed from a kneeling figure in supplication even exceed the dehumanized array of Black bodies. However, the question “Am I not a man?” was brought up again two centuries later. In 1968, during the Memphis sanitation strike provoked by the death of two employees and demanded betterwages and working conditions, “I Am a Man!”signs were used as an answer to the question. American journalist Ernest C. Withers used a camera to capture the moment when the sanitation workers used “I AM A MAN” as their statement to affirm their unity, their humanity, and their demand for respect, and this picturebecame one of the most recognizable images from the Civil Rights Movement. Inspired by this photograph, contemporary artist Hank Willis Thomas remixed the texts and created a series of paintings. As narrated by the artist himself, he was born in 1976, and he was struck by just eight years before he was born, it was still necessary for Black people to make a large public protest to proclaim their humanity. During the following twenty years, when Thomas grew up, the dialogue shifted from “I am a man” to “I am the man,” which also signified a transition from a collective statement of human rights to a confident but sometimes selfish personal statement of individual existence and privilege. By reading through and thinking about the different statements in each frame, Thomas hopes to convey the message that rather than evaluating ourselves based on else's standards of reality or value, the greatest elation that we could all have is to recognize that our consciousness is the greatest gift.