The Visualized Regime of Liberty

“Unable to sustain its form, the plantation complex entered a period of crisis, competing with a new visualized regime of ‘liberty,’. . .”

-Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality

The nineteenth-century antislavery movement made use of the promises of the American Revolution, foremost the promise of liberty, which the nation was struggling to define. These three objects all touch on history as a territory under constant, and often violent, negotiation. These are impressions, reproduced and reimagined, that ask: in the visualized regime of liberty, what do images leave?

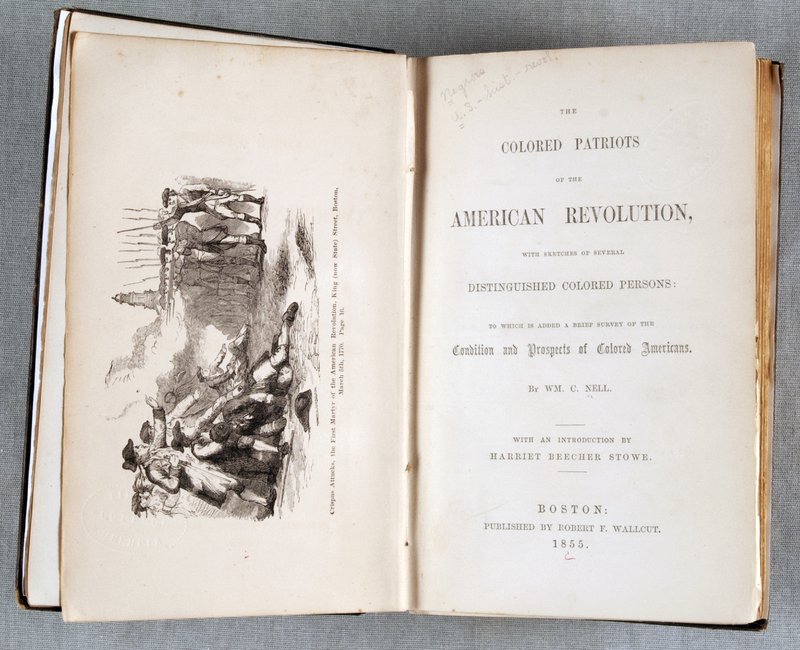

In The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution William C. Nell draws attention to the role of Crispus Attucks, the first person killed in the American Revolution. Published in 1855, this engraving was the first image to acknowledge Attucks’s role in the Boston Massacre of 1770. Attucks is notoriously absent from the widely circulated engraving by Paul Revere of the same scene. The two prints include similar compositions: a street scene with a strong diagonal separating the British firing line from the cluster of unarmed victims. Nell, however, crops the image so that only the bell tower remains of the streetscape, and shifts the axis of violence so the group of victims comes to the fore. Attucks, cradled by a kneeling man, and defended by another who stands with his arm outstretched, is the tragic subject of the scene.

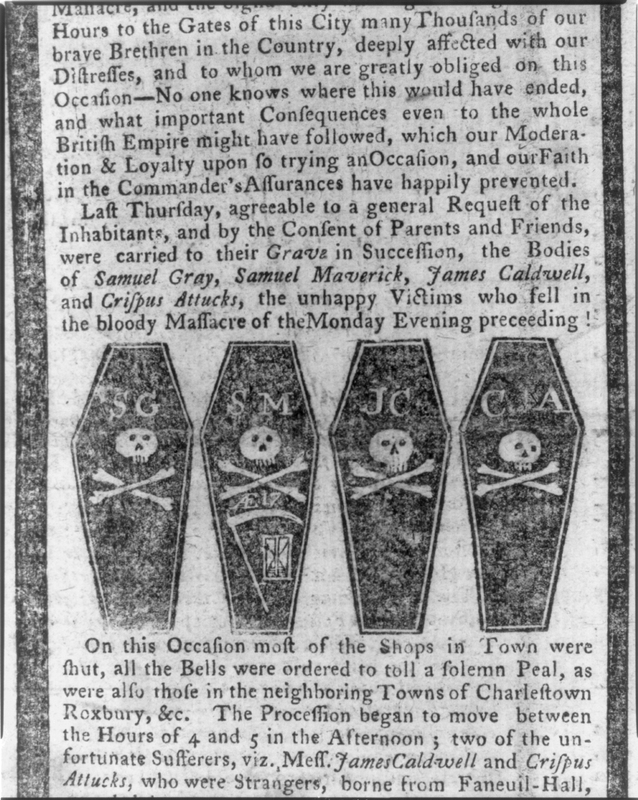

The image captures Attucks in his final moments of heroism. In an essay from 1932, Mary Church Terrell highlights the role of Black soldiers, particularly Attucks, in the American Revolution. She sets the stakes of his involvement high by quoting Daniel Webster’s speech from Bunker Hill, in which he refers to the Boston Massacre as nothing less than the inauguration of the independent nation: “From that moment we may date the severance of the British empire.” Terrell concludes, “Thus did a runaway slave start the struggle for independence which George Washington brought to such a glorious end.” Terrell’s words may seem to bury Attucks under Washington’s fame, but in referring to Attucks as “a runaway slave,” Terrell fills in a historical gap. Attucks’s name was not forgotten, but his identity was erased from the visual record. In the report from the Boston Gazette on March 12, 1770, which also published Revere’s engraving for the first time, four coffins appeared to commemorate the victims. The uniform schemas of the coffins, each marked with the initials of a martyr and the skull and crossbones, gloss any differences between the men. Attucks’s easy inclusion in death belies his exclusion in life. The four men who died in the Massacre were buried together in one grave, which reads: “Long as freedom’s cause the wise contend, / Dear to your country shall your fame extend, / While to the world the lettered stone shall tell/ Where Caldwell, Attucks, Gray and Maverick fell.” Equated for one historical purpose, Nell and Terrell take up Attucks’s perceived difference for their own projects of abolition and civil rights. Even in death Attucks is contested.

Attucks died for a liberty that did not include him, and his death emblematizes the shadowy duality of freedom. “A mulatto man, named Crispus Attucks” is mentioned in the newspaper report, but no man of color appears in the print that illustrates the scene. While Attucks is described by racial terms in the text of the report, there is no visual marker to identify him in the engraving. The Attucks of the text is nowhere to be found in the image: he has, in the words of Agnes Lugo-Ortiz and Angela Rosenthal, “[been] erased. . .from the masterly field of vision.” In framing Attucks as a martyr of the American Revolution, Nell, a Black abolitionist, is redrawing Black Americans into the country’s founding myths. Wendell Phillips writes in a prefatory note to the volume that Black men are “patriotic though denied a country.” Similarly, this engraving asserts an essential freedom for Black Americans, albeit one entwined with death. Landless patriotism and lifeless freedom are just two contradictions Attucks embodies. Those contradictions are precisely why the memory of Attucks as a Black man and a patriot has been so often a contested site of political meaning.

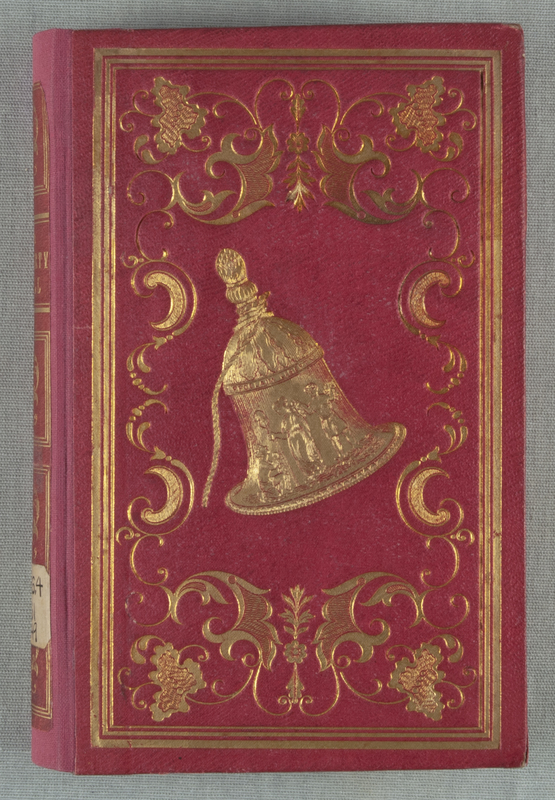

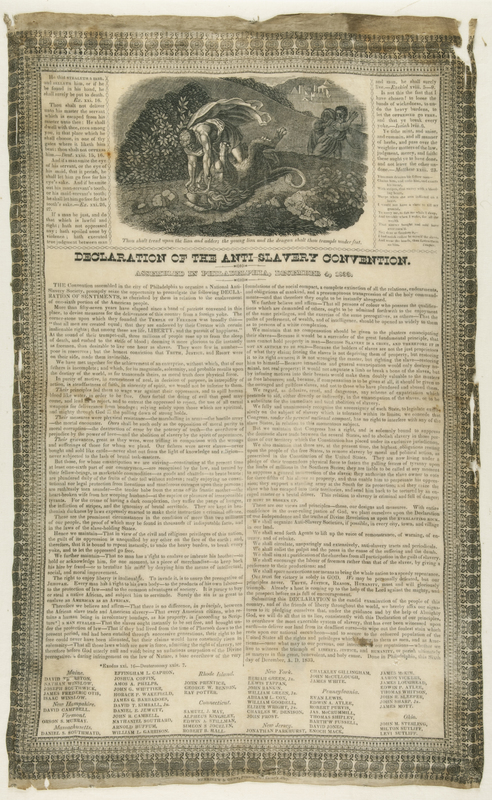

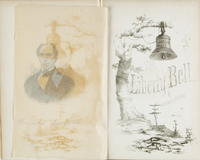

Attucks appears in Nell’s book as a hero, who, with his death, demonstrates both bravery and helplessness. The antislavery gift-book The Liberty Bell, an anthology published annually between 1839 and 1858, made use of a similar rhetoric. As Ralph Thompson has outlined, the publication, organized primarily by a group of women, pulled from American and European authors to make emotional appeals for the eradication of slavery. The books circulated among those already involved in the cause, largely as subscriptions or at abolitionist fairs, where they were sold. By the late 1840s the gift-book form was on its way out, the vestige of a more romantic period that was incongruous with the coming war. Gift-books presented the story of slavery in a conventional manner, with slave and master in the roles of hero and villain. The illustration that adorns the title of the Declaration of the Anti-Slavery Convention likewise calls on a binary heroism. The woodcut shows Hercules strangling the Nemean lion, whose golden fur was impenetrable to weapons. The lion was the first of twelve labors Hercules completed in penance for the murder of his wife and children. It stands over the list of resolutions, passed by abolitionists at the antislavery convention held in Philadelphia in 1833. They called for the establishment of a national antislavery society and enumerated their goals not only for the emancipation of “one-sixth portion of the American people,” but also “that the paths of preferment, of wealth, and of intelligence, should be opened as widely to them as to persons of a white complexion.” Biblical quotations denouncing slavery surround the print, which appears on an elegant support of satin. The defeat of slavery becomes a heroic act of physical strength, although the manifesto speaks only of moral might.

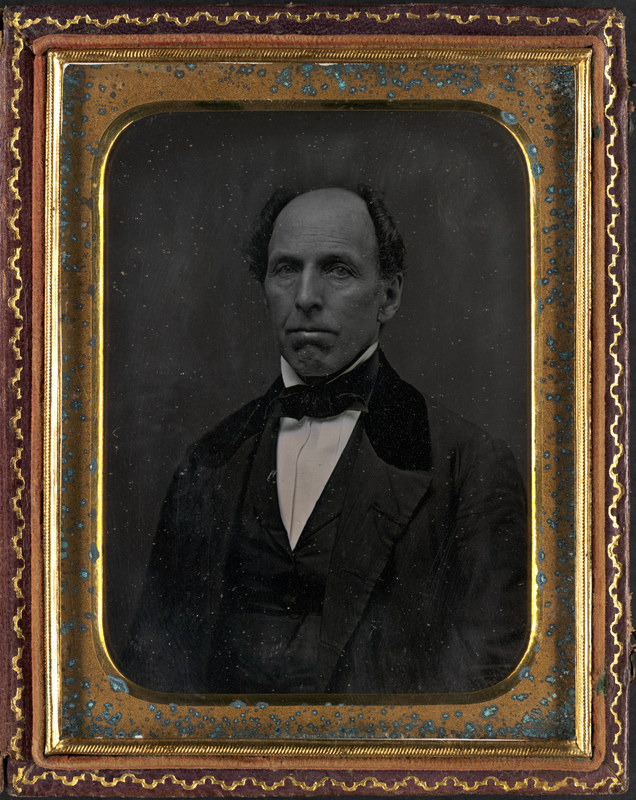

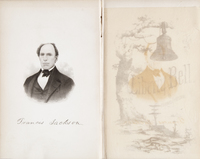

The abolitionist preacher William Lloyd Garrison christened a bell, forgotten since the Revolution, “the Liberty Bell,” turning it into a symbol of abolition, and giving material form to an evasive concept. The liberty bell hangs from a tree, inscribed on its shoulder with the phrase “proclaim liberty for all.” On the distant horizon, a slave ship sinks into the water. Broken shackles and a shattered sword are scattered on the ground, suggesting an absence that is not really absent. As the liberty bell tolls, the Black body disappears. In this copy of The Liberty Bell, the images of the liberty bell and Francis Jackson, the Boston abolitionist and historian whose portrait opens the book, have offset, producing doubled versions of themselves. Jackson’s engraved portrait has bled through to the first two blank pages of the book. His figure has run where the ink was heaviest, so his faceless shadow appears twice before his portrait, not unlike he would appear on the silvery surface of the daguerreotype from which it draws. On the onionskin paper between the pages are the ghosts of the two prints, the darkest parts of which appear again in sepia tones. As the pages of the book turn, Jackson’s body and the bell hanging from the tree are briefly overlaid on a single sheet.