Be Not Dismayed By Their Archives

“Be not dismayed by their archives. For their tabulations, calculations, and violent ministrations do not define us. . . . I am. Silence. Absence.”

-Sasha Turner, “1619?”

Sasha Turner’s essay “1619?” argues that the archives of Atlantic slavery and emancipation were not designed to, and indeed could not, capture the fullness and depths of Blackness. Drawing from the Oberlin College Archives and the Oberlin College Library Special Collections, in particular its Anti-Slavery Collection, this exhibition explores Turner’s assertion through analyses of the materials and legacies of anti-slavery visual culture in the long nineteenth century. To gain support for their causes, the makers of the objects displayed here created a confused, multifaceted archive that in many cases figured Blackness as alternately violent, assertive, or submissive; fugitive or patriotic; valorized or exploited. But above all, they make clear that the project of Black freedom remains incomplete.

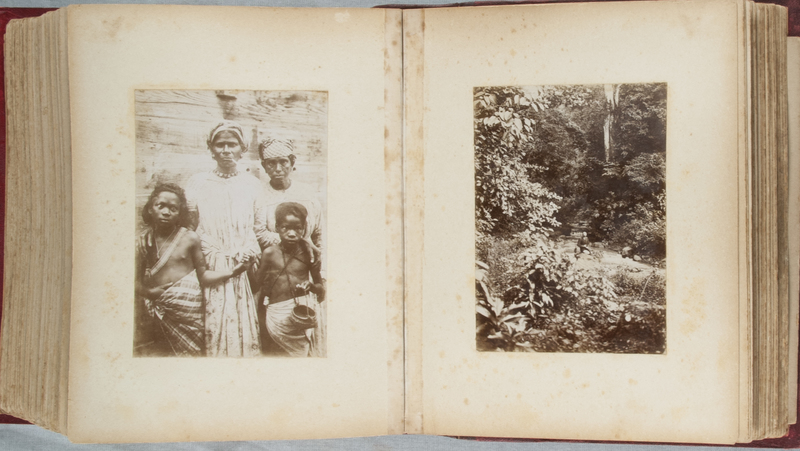

The album exhibited here, produced in the last decade of the nineteenth century, testifies to the blurry boundaries and strategies of the visual culture of slavery during this period. Containing over three-hundred gelatin silver prints, each glued in by hand, it traces the trans-Atlantic journey of the crewmembers of an unrecorded French frigate. The ship transported goods from Madeira to Portuguese West Africa and then to Martinique, where the spread below was shot. Here, the album’s creator juxtaposed a close-cropped portrait of four people, at left, with the image of a man – likely a member of the ship’s crew – nearly enveloped by tropical foliage. This album contains no writing: no labels with which to identify those depicted, and no descriptions of the images’ content. In the wake of that absence, what histories emerge when we consider that the crew of this frigate reproduced the common journey of slave ships from Africa to the Caribbean? What stories are written on the faces of those pictured in Martinique, persons likely descended from the survivors of those voyages? And why, finally, might the ship’s white French crew needed to capture them in this album?