The History of Abolition

“The history of abolition is a white-evolved historical fiction in which the slave is given the gift of freedom by a beneficent patriarchy and by a noble nation.”

-Marcus Wood, The Horrible Gift of Freedom

Thomas Clarkson's river-map and the signatures in Anne Thompson's album visualize genealogies of white abolitionists. Clarkson's map commemorates the British Parliament's prohibition of the international slave trade in 1807, a year before its printing. He uses a river map to depict the ways different abolitionists’ ideologies of freedom played off of each other. Thompson’s album evidences how the women's rights movement sprang out of abolitionism even as it excluded women of color. Anne Thompson attempted to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in Britain in 1840, until its organizers, many also included in Clarkson's map, ejected her and several other women for their gender. These same women went on to organize the Seneca Falls Women's Rights Convention in the United States. Both objects consist of the names of prominent white abolitionists, and the project of both books is to preserve the histories of people involved in social change. These books are both artifacts of what Marcus Wood calls the “history of abolition,” in which white men-- and occasionally white women-- are the only permitted saviors.

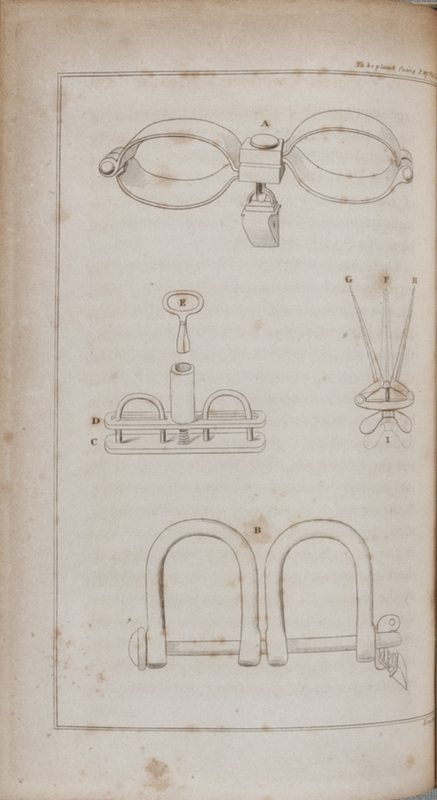

Thomas Clarkson’s book functions as a prime example of the erasure of enslaved people from the “history of abolition.” Thomas Clarkson dedicated his book to the government ministers who passed the Slave Trade Act of 1807 through Parliament. Inside, he honors the work of abolitionists across Britain. Clarkson includes diagrams of empty manacles and drawings of other instruments of torture. These drawings are meant to inspire horror, and by being depicted as empty, they allow the viewers to imagine these devices being used on their own bodies. The schematizing nature of these images alienates these objects from the people who used them, who would look a lot more like the abolitionists themselves than the enslaved people who actually experienced these tortures.

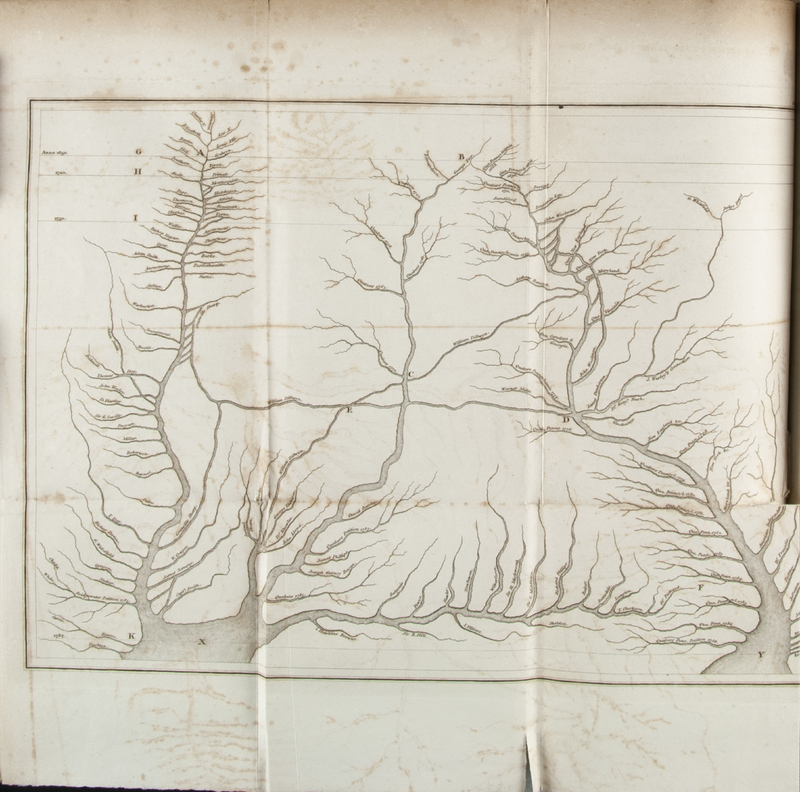

Clarkson’s "map" further demonstrates the way the British abolitionist movement prioritized white people. The "abolition map "is better described as a genealogy of British abolitionist thought presented as a group of rivers flowing to the ocean. On the page opposite, Clarkson writes that the map shows the "so many springs or rivulets which assisted in making and swelling the torrent which swept away the Slave-trade." The reason he chose a map as the format was “to bring together [the different strands of abolitionism] before the reader so that he may comprehend the whole of it at a single distance.” The idea of “total vision,” as Jill Casid terms it, points to the colonialist bend to British abolition. “Total vision” was central to oversight on the plantation. Slaveowners developed oversight to have “total vision” of their slaves and keep them under control, and to smother rebellion.

These strategies of total vision, off the plantation, were also central to British colonial control in India, even after Britain banned slavery. Clarkson represented this ideological family tree with the metaphor of rivers, which open into a sea. Clarkson used a map of water, a technology developed with the transatlantic slave trade, to display his and his colleagues' ideas. The British Empire's dominance of the sea became the force behind the abolition of the slave trade, which meant there was no need to acknowledge how Britain developed its naval prowess to create the very same institution it celebrated itself for wiping out. Clarkson’s narrative shows how British popular consciousness transformed the memory of the slave trade into a self-congratulatory narrative of its abolition. When Clarkson’s book lists the names of popular abolitionists, he credits these people with influencing the whole British Empire, granting them—and himself—a place in the historical canon that the book prioritizes over the actual cause itself.

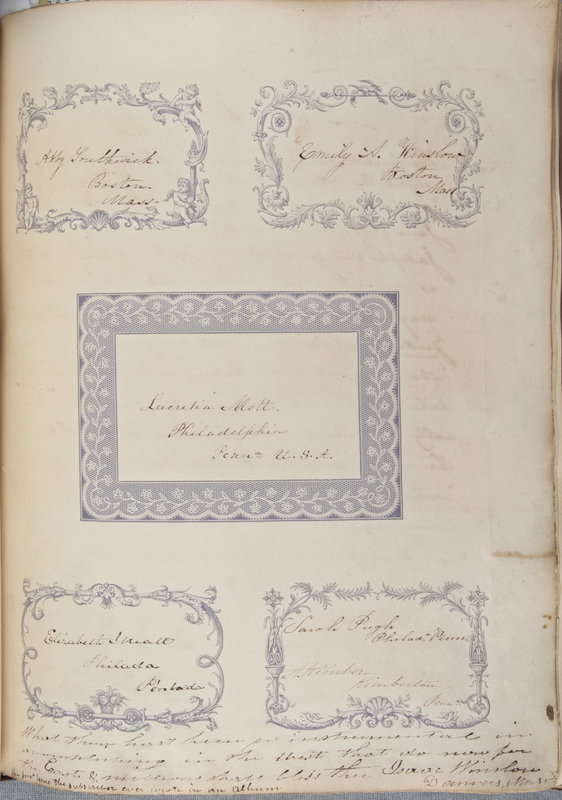

The World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1840, at which Thomas Clarkson was the keynote speaker, further shows the power of name recognition in British abolitionist circles as an indicator of inclusion and exclusion. Name recognition for British abolitionists is an essential feature in both Clarkson's map and Anne Thompson's album. Clarkson created his river-map to preserve and enshrine the names of British abolitionists he saw as influential, but Thompson’s album shows how that kind of name recognition could be used to further one’s position as an abolitionist. Nathaniel Peabody, Lucretia Mott's co-delegate to the 1840 conference, recorded the events of the World Anti-Slavery Conference in 1840 in Thompson's album because of the power her husband’s name recognition gave her. He states in an entry describing the conference's rejection of several American women, close to the list of signatures of those women, that her album was appropriate because of who her "devoted husband" was, and how influential he was on anti-slavery. Other than that, there is almost no evidence of Anne Thompson in her album. It functions more like an anthology of her husband's deeds than anything that documents the events of her life. Documents of George Thompson’s life dominate the album, which also demonstrates how important written documentation was to abolitionism. Yet, Anne Thompson's autograph album is also an example of high society tradition becoming folded into activism, or vice versa.

Anne Thompson's feelings on the concept of women's rights are, then, completely undocumented. But despite this exclusion, her album documented the story of these events in a note. It also contained a list of signatures, with names and cities of origin, that kept the record of who participated. Albums generally were considered to be sites of female subjectivity, but the connections documented in albums became the basis of social organizing and rebellion for women. Scrapbooks served as mnemonic devices to preserve women and the things they cared about in a realm where, on the one hand, it would not intrude on men, and on the other, it was entirely their own. The women whose signatures are present on this page organized the Seneca Falls Conference. Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton met at this event after being rejected by the British abolitionists for their gender. The page of signatures, which features these women’s names and home cities, serves as a relic of their meeting, enshrined in the specifically feminine form of the album. Even the names themselves are embellished in curlicues, typical of scrapbooks at the time. Yet despite being born out of the abolitionist movement and created by abolitionists, Seneca Falls and the entire American feminist movement’s relationship with race is fraught. Frederick Douglass was the only person of color present at the Seneca Falls conference. No women of color were invited or were present. The connection between the two movements, women’s rights and abolitionism, prioritized white women abolitionists over Black women, enslaved or free.

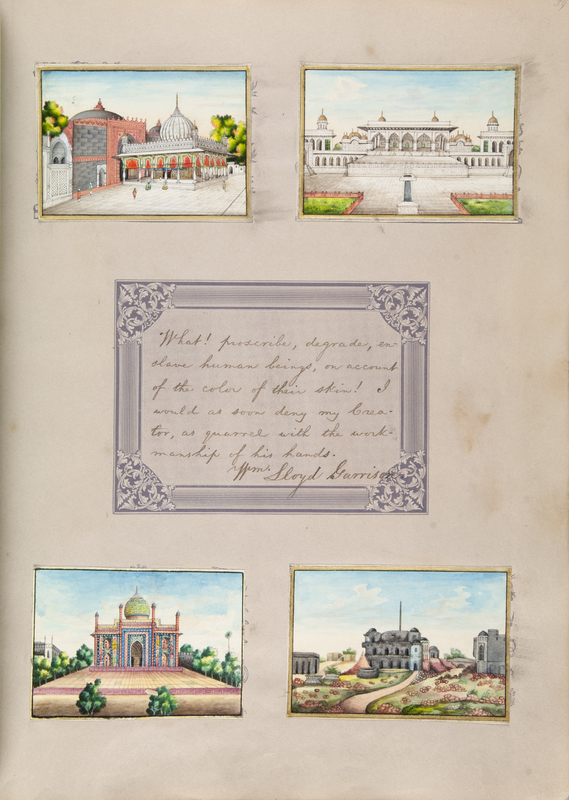

Abolition as a concept separate from slavery is a white fantasy, and these objects reflect narratives built by and for white people far better than they reflect anything about the realities of Transatlantic Slavery. The exclusivity of who was allowed into the abolitionist movement shows that it was more self-serving than moral, the American feminist movement did not include people of color. The enterprise of documenting abolitionism was inherent to gaining power within the abolitionist movement, which was more important than the actual ideas espoused by abolitionists. On one page in Thompson's album, brightly colored images of India surround an anti-slavery quote. The Thompsons served as envoys to Delhi for the British Empire. Only 20 years after the 1840 conference, Britain would claim control over India and create the British Raj, and enslaving thousands of Indian people. This page is a visual example of how abolitionist clout could be leveraged to give someone power within the imperial structure. By documenting George Thompson’s deeds and positions, Anne Thompson generates the power of historical memory for her husband that he used to gain a prominent imperial position. And working for the empire was counterintuitive to abolitionist ideals. In “ending” the slave trade, James Walvin notes, Britain found ways to profit off of slavery through privateering, which monetized their policing.

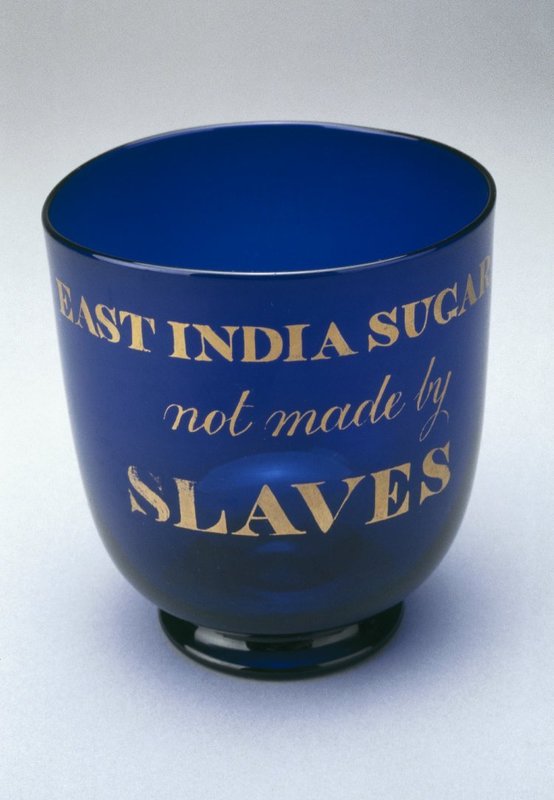

For British Christian abolitionists, their empire was something to be proud of in its role in "ending" the slave trade, even when the actions of the empire went against their conceptions of human rights as much as slavery itself did. British people popularized abolition and anti-slavery as fashionable, even as the British Empire continued to profit off of slavery. One such example is a sugar bowl from the British Museum, an object which shows how the wealthy and aristocratic began to make the movement as much about upholding decorum and conspicuous consumption as it was about ideological principle. As abolition became morally and materially fashionable, the British people saw the empire as inherently advancing abolitionist causes and ideals. If the Empire was abolitionist, all of its actions were in the spirit of abolitionism, no matter what they were. Clarkson’s map and Thompson’s album, as they assert the importance of the individual abolitionist to abolitionism as a whole, function to preserve this attitude more than they do anything about slavery.

Clarkson's map and Thompson's album both serve as genealogies of social movements. Clarkson's list is deliberate, while Thompson's album serves as both a list of names of women’s rights activists and a de-facto archive of her husband's life. One of the things they have in common is that these objects were saved and preserved, which was an intention of their creation. Documentation was ultimately a project in the service of abolitionism, rather than abolition. These objects, and the texts within them, were created by white people for other white people. They commemorate commemorating slavery and memorialize abolition while excluding the voices and experiences of Black people. Histories of abolition prioritized abolitionists rather than abolition itself and are over-represented in archives not despite of this priority, but because of it.